Skating on Thin Ice

Skating on thin ice

By Sam Laskaris

Oct 30, 2001, 11:54

|

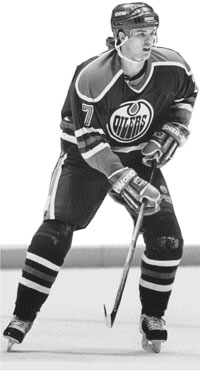

| Arnott: No place like home. ©BBS |

The name Forbes Mitchell doesn’t appear on any Toronto Maple Leafs scoring summaries. Yet Mitchell believes he’s played an integral role in the club’s recent successes.

Mitchell is the chief engineer at Maple Leaf Gardens, Toronto’s home rink. His duties include overseeing the operation and maintenance of the arena’s ice.

“The most exciting part has been the last couple of years,” says Mitchell, who is in his 17th season of working at the rink, which is frequently referred to as the Mecca of hockey. “The Leafs have done well. They made it to the final four (in the Stanley Cup playoffs) both times. You feel you’ve done something towards it.

“Some players might think differently. But if you have million dollar players out there, they can’t do it all themselves. They’ve got to have good ice to skate on.”

Mitchell, 65, is also an avid hockey fan. He’s traveled to several other National Hockey League rinks, and like numerous pro players, he considers Edmon-ton’s Northlands Coli-seum to have the best ice, with Calgary’s Saddle-dome a close second.

NHL arenas with reputations for less-than-ideal ice conditions include Madison Square Garden in New York, the Boston Garden, as well as the California (Anaheim, Los Angeles and San Jose) and Florida (Tampa Bay and Miami) rinks.

Give the man air

“Air conditioning is the key,” says Mitchell, who was born in Aberdeen, Scotland and emigrated to Canada in 1956. “I’d say my ice would be at least 25% better if we had (air conditioning) here. If we had it here, I’d say we’d be on par with Edmonton and Calgary.”

Making ice for an NHL rink is no simple process. At Maple Leaf Gardens, the action begins in the engine room, located on the building’s west side. The word “room” is used loosely here as most houses would fit into it; it’s about 90 feet long and 50 feet wide.

The room includes mammoth ammonia and brine (a salt solution) compressors. A concoction of the two is carried via plastic pipes from the engine room to the playing surface where the ice is formed.

Mitchell says the ideal temperature of the ice for an NHL game at the Gardens is 17 degrees. Before a game starts, however, he’ll try and have it a few degrees below that. His reasoning?

“When you turn on the TV lights and the crowds start coming in, it gets up to 18 or 19 degrees in no time,” he says.

Maple Leaf Gardens continues to get hotter as games progresses. “If I can go through a game and hold it at least at 23 degrees, I’m okay,” Mitchell says.

As for the ideal thickness for ice at Maple Leaf Gardens, it’s between three-quarters of an inch to an inch. But when there’s an ice show at the Gardens, another half inch tends to be added.

“You’ve seen how high they jump,” Mitchell says of figure skaters. “And when they come down, they jump right into the cement. We’re always patching the floor when they’re through.”

Mitchell adds there needs to be more care of ice surfaces now than there was 10 or 15 years ago. That’s because players are bigger and stronger than they used to be, and their raw mass can inflict plenty of damage to the ice.

“They’re giants now,” he says. “A lot of them are 6-foot-2 or 6-foot-3, and they’re 200 pounds. And then look at somebody like (Pittsburgh Penguins center Mario) Lemieux. He’s even bigger than that. With guys this big now you have to keep a closer eye on the ice or it will give you a lot of problems.”

Practice hurts

Mitchell doesn’t mind seeing his masterpiece, the ice surface, getting worked over during NHL games. Practices, though, are a different story.

“During games you get to flood it after every period,” he says. “But for some practices they go two hours straight and they cut it up pretty good. It’s not as if I’m going to go out there halfway through the practice and say ‘Okay, everybody off the ice’.”

Training camp is not an ice-maker’s favorite time either. “You get about 60 guys trying out for the team,” Mitchell says. “And you get them all dancing around out there. They tear it up pretty good. You’re always glad to see the end of training camp.”

As for the majority of NHL players, they’re often glad to have the opportunity to skate on the above-average ice in Edmonton.

“This informal reputation is one we’ve heard of for many years,” says Kenn Bur, communications supervisor for Edmonton Northlands, which sub-leases its rink, the Coliseum, to the Oilers. “NHL players have noted for many years that they like the ice here.”

Bur says there are several reasons why the Coli-seum’s ice is so highly regarded.

“It’s not just one thing we do,” he says. “There’s an extreme attention to detail. One thing we do is use soft water. Many arenas don’t. Every detail related to the ice is controlled as much as it can be. We have some people here who take quite a lot of pride in working on the ice surface. These are the people behind the scenes, in some cases who have devoted their lives to learning about what makes excellent ice.”

It didn’t take Edmonton Oilers center Jason Arnott long to find out his home rink has the best ice in the NHL. His teammates had told him the Coliseum ice was tops in the league. He found out for himself about the midway point of last season, when he had made the tour of all the other NHL cities.

A smooth surface

What’s so great about Edmonton’s ice?

“It’s the smoothness,” says Arnott, who was a finalist for the 1994 Calder Trophy, awarded annually to the NHL’s top rookie. “It’s not too hard and not too soft. And it’s not as snowy as other rinks.”

Arnott, who was selected in the first round, seventh over-all, at the 1993 NHL Entry Draft, says pro players usually reserve judgments on ice conditions until after the morning, pre-game skate.

Arnott adds that depending on which NHL rink they’re playing in, players often ask the team trainer to sharpen their skates a bit differently. For good ice surfaces, a thorough sharpening is often requested while there’s limited sharpening needed when playing on poor ice.

“On bad ice I ask for no sharpening,” Arnott says, “it makes gliding a lot easier, and so you’re not digging into the ice.”

Like most NHL players, Philadelphia Flyers star center Eric Lindros considers Edmonton and Calgary to have the best ice surfaces in the league. A pair of his other favorites include the Winni-peg Arena and Philadelphia’s home rink, the Spectrum.

Depending on which rink he’s playing in, Lindros says he has to adjust his game.

“Playing a finesse game is a lot tougher when you have bad ice,” he says. “You’re not going to have pretty plays.”

Logically, pucks are going to bounce more on bumpy surfaces than they will on smooth ones.

Safety a factor

Though both teams involved in a game have to play with the same conditions, complaints about certain NHL ice surfaces are common, Lindros says. “Certainly everybody gets (peeved) off when the ice is bad,” he says. “At times it’s not even safe, especially with games at neutral ice sites. It’s not a big priority for them. They usually have not had NHL ice in there.”

During his rookie season in 1992-93, Lindros had some bad luck with ice at the Great Western Forum, home of the Los Angeles Kings. “I was just following through on a shot in the warmup and I hit a rut in the ice,” he explains.

Lindros, who was just coming off a ligament injury to his left knee, was sidelined for nine games following this incident.

Hartford Whalers Geoff Sanderson says NHL players aren’t constantly worried about getting injured on a bad patch of ice. “Usually the linesmen do pretty well to fix them up when they see them,” he says.

Because each rink is different, however, players have to make adjustments to their game.

“On bad ice the puck bounces around a lot more and it slows down your skating time,” says Sanderson, who is the only player currently in the NHL who was born in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

No matter what the ice looks like before a game, players can expect it to be considerably worse for wear later on.

“By the third period it gets really chewed up,” Sanderson says. “In the last few years we’ve really noticed it in our rink. We’ve played a lot of time in our own end.”

During Sanderson’s first three seasons with the Whalers, Hartford’s cumulative record of 79-141-28 was nothing to brag about. But at least he’s learned a lot about ice.

This first appeared in the 11/1994 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2001 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®

http://farmaciaasequible.com/# farmacias cerca de mi abiertas hoy

buy enclomiphene online enclomiphene testosterone or enclomiphene buy https://www.google.dm/url?q=https://enclomiphenebestprice.shop enclomiphene buy enclomiphene online enclomiphene online and enclomiphene online buy enclomiphene online

https://enclomiphenebestprice.com/# enclomiphene for men

enclomiphene buy: enclomiphene for sale – enclomiphene for men

https://rxfreemeds.com/# RxFree Meds

enclomiphene for men: enclomiphene best price – enclomiphene for sale

la roche posay antimanchas opiniones se puede comprar mycostatin sin receta or aboca group https://chyba.o2.cz/cs/?url=https://farmaciaasequible.com la botica sevilla este tadalafilo 5 mg 28 comprimidos precio farmacia espana and farmacia envio 24h fsrmacia

https://enclomiphenebestprice.shop/# enclomiphene for sale

https://rxfreemeds.shop/# tricare pharmacy crestor

buy enclomiphene online: buy enclomiphene online – enclomiphene buy

enclomiphene for men enclomiphene online or enclomiphene best price https://clients1.google.dk/url?q=http://enclomiphenebestprice.shop buy enclomiphene online buy enclomiphene online enclomiphene for men and enclomiphene for sale enclomiphene