Jeff Skinner | 2011 NHL Awards Red Carpet

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews Jeff Skinner about being nominated for the Calder trophy.

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews Jeff Skinner about being nominated for the Calder trophy.

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews the Dallas forward about being nominated for the Lady Byng.

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews the Chicago Blackhawks captain about being nominated for the Selke and the Jets returning to his hometown of Winnipeg.

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews Craig Patrick about presenting the Executive of the Year Award.

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews Corey Perry about his standout season with the Anaheim Ducks.

Patrick Perrett of Hockey Player Magazine interviews Lappy about being nominated for the Masterton and playing on his line in Park City.

By Stan Fischler

Oct 29, 2001, 19:32

|

| ©BBS |

Everything—that is everything —was against Joe Mullen becoming an NHL star.

He was born in New York, when nobody from Manhattan had ever made it to the NHL. They said he was too small.

Another rap was that roller hockey players, which Mullen was, don’t have ice instincts.

On and on went the critics, and on and on climbed Mullen, proving them wrong every step of the way.

From the sidewalks—literally—of New York to Boston College, then to Salt Lake City of the Central Hockey League. Up, up and away he went, like a micro-Superman-on-skates, outpacing the knockers and making well-respected hockey men look stupid in the process.

By all rights Joey should have spent his career starring with the Rangers. His father ran the Zamboni machine in Madison Square Garden. His father would have given anything for his son to play for the Broadway Blueshirts.

But like so many others who underestimated Joe Mullen, the Rangers said “thanks-but-no-thanks,” and Joey signed with the St. Louis Blues. He played his first NHL game during the 1980 playoffs.

The rest, as they say in Montreal, is histoire. At age 35, Mullen’s stride, savvy and scoring ability is as strong as it ever was. What’s more, he has just become the first US-born 1,000-point scorer in NHL history, and taken home (along with brother Brian) the Lester Patrick Trophy for service to hockey in the United States.

In the following interview, Mullen discusses everything from his roller hockey roots to his future as a youth-hockey coach.

Do you remember your first pair of hockey skates?

You have to bear in mind that where I came from—in the middle of Manhattan, near the old Madison Square Garden—the first skates were roller skates. The clamp-on kind. There were two basic brands. Union Hardware was the cheaper kind and Chicagos were the better ones. If you were real serious about roller hockey, eventually you graduated to shoe skates.

Diagonally across from the old Garden, on Eighth Avenue, there was a little store called the Princeton Skate Shop. That’s where the guys got their shoe skates, and you also could get ice skates as well. Later on it was where we had our ice skates sharpened.

What kind of sticks did you use on the streets of Manhattan?

The most popular stick when I was a kid was the Northland, because most of the NHL players used it. Then there was the Vic. We used just about anything we could get our hands on as long as it wasn’t completely broken.

Describe the difference between roller hockey in the late 1960s and today.

The puck wasn’t very sophisticated. It was just a hunk of electrician’s tape with a hole in the middle. If the playing surface was relatively smooth, the tape-puck moved pretty well. There was no such thing as in-line skates then. We used the four-wheeled kind and when the wheels wore down you could replace each one.

How different was it from ice hockey?

It took longer to stop, and if you went down to block shots a lot, you’d rip your dungarees or whatever. The puck was lighter, but you couldn’t shoot it quite as fast and, of course, you couldn’t move as fast on the macadam (the broken stone surface) as you could on ice.

What kind of carry-over value did roller hockey have for ice hockey when you moved on to Sky Rink?

There was quite a bit, because the stickhandling on the dry surface was tough. So if you could handle the puck in roller hockey, you could do it on ice, for sure. Same with shooting; if you could shoot a puck from macadam, you certainly could on ice. Funny, but the skating stride was different and when I went from roller to ice, my ice hockey stride was choppy. It wasn’t until I got to college where I smoothed it out a bit. In roller hockey, it was more like running. The big difference was that on ice, the puck slid better and moved quicker.

What aspect of roller hockey did the most for your ice hockey career?

Let me say right off the bat that if it wasn’t for roller hockey, I wouldn’t be where I am today. The thing that was so important about the roller side was that it was so easily available for me. I’d walk out of the house, go across the street and I would be playing. It didn’t matter if it was hot or cold, raining or snowing. The availability gave me a chance to play every day, and since I played every day I was learning how to shoot, pass and stickhandle—all the assets I would need for ice hockey. I’ve said it before: roller hockey can’t do anything but help kids who want to become ice hockey players.

Who, specifically, helped you?

Besides my younger brother, Brian, I had two older brothers who were excellent roller hockey players. Kenny was a center and Tommy a right wing. Kenny has a lot of hockey sense and his style reminded me of Bryan Trottier. Tommy was a terrific shooter who had a knack of scoring from bad angles. He always found a way of putting it in the net. Kenny moved up to ice hockey and did well in the (New York) Metropolitan League and then played a year at Northeastern. He might have gone farther, but those were the times when Americans were just making some inroads into the game and he was a little before his time.

What did you learn from them?

Just by watching them play, I was able to see things about the game that I didn’t know before. Then, I would watch the Ranger games on TV and learn from the pros. I put two-and-two together and became a smarter player.

Who did you play for at the start?

I was lucky. The Sacred Heart Church in the neighborhood had a lot of teams. We were in the Police Athletic League, YMCA League and the Catholic Youth Organization League. By the time I was sixteen, I was playing in a men’s league out of Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn.

It’s amazing, considering your father’s job in the Garden and the fact you lived across the street from the arena that you were never picked up by the Rangers.

Actually, I almost was. This was after I had signed with St. Louis and was playing in their minor league system. Craig Patrick was running the Rangers at the time and the Blues had called me up for a game. I didn’t know it at the time but Patrick was watching me in the hopes of swinging a deal with the Blues. As a matter of fact, he came very close to making the trade—and then I loused things up. In the game he was watching, I scored a goal and must have looked good enough for the Blues to figure that they shouldn’t let me go. After the game, I was in the hotel and Craig happened to follow me into the elevator. He looked at me, smiled, and said, “You had to go and score a goal tonight, didn’t you?” I said, “Whaddya mean?” Then, he said, “If you hadn’t scored, I had ya!” And that was that. One less goal and I would have been a Ranger.

You got some good advice about making the transition from roller to ice hockey. What advice do you give to youngsters nowadays?

I tell them to play as much as they can, whether it’s on roller skates or on the ice. Shoot the puck, listen to the coach and, most of all, work hard.

You sound like you’ve been coaching already.

I have. During the lockout, I was coaching my kids. Ryan is 13, Michael is 11 and Patrick is eight. I try not to push them, but I want them to have fun. I coached three different teams and it was very rewarding, particularly when you see them following through on something you taught and they do it right.

This first appeared in the 05/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2011 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®

By Bob Cunningham

Oct 23, 2001, 18:14

Chris Pronger was the second player taken in the 1993 NHL Draft, mainly because the Hartford Whalers felt the 6’6”, 215-pounder had the tools to become another Paul Coffey.

At Peterborough, Pronger tore up the Ontario Hockey League, tallying 139 points in 125 Major Junior games. And with his extraordinary size, the Whalers believed they had the type of player who could dominate at both ends of the ice.

But Pronger is human. He entered the NHL last season and, by his own admission, was less than himself in his first few weeks at hockey’s highest level. He knew he belonged in the NHL, but simultaneously believed he needed to crawl before walking.

“I was a little hesitant because I didn’t know what to expect,” says Pronger, who indicated that his reluctance to showcase his own skills caused him to endure a less-than-ideal first half of his rookie campaign. “Once I started to relax, I began to play better.”

The common error many young defensemen, and even some forwards, make is to play scared. Rather than concentrating on aspects of the game that will help their team win games, these intimidated youngsters work instead at avoiding stupid mistakes that lead to losing.

It applies at any jump in level, whether it be from Juniors to the NHL or from the 10-and-11 year-old division to the 12-to-13 class.

Confidence a “must”

“You don’t want to be cocky, but you definitely have to be confident in what you’re doing out there,” Pronger says. “When you’re a young player, or a rookie, bad games are a given. What you have to do is learn how to work your way through it.”

Pronger played in 81 games last season, amassing 30 points along with 113 penalty minutes. Those numbers are certainly nothing to be ashamed of, but Pronger knows he’s capable of much higher production. And he entered his sophomore season bent on reaching the level Whalers management had in mind when they picked him ahead of Paul Kariya and Jason Arnott, among other promising youngsters.

“I believe your first priority should be to take care of your own end first,” he says. “But when the (scoring) opportunities are there, you have to go after them. In my rookie year, I didn’t feel as confident as I would have liked on the offensive end. There was no reason for me to think that way.”

Still, Pronger did have a positive effect on his new team. The Whalers allowed almost 60 fewer goals last season than they did in 1992-93.

“I did a lot of work on the basics. I worked hard to help out at both ends, especially in the second half of the season,” he recalls. “I worked a lot on foot speed.”

The frantic pace of the NHL leaves most rookies in awe. Pronger said that he thought he had a grasp of the Bigs until he played in his first NHL game.

“Not only is the tempo so much faster, but everybody gives 110 percent on every shift of every game,” he says.

That’s a feeling most players experience whenever they’re promoted to a new level of the game; it’s not a scenario that’s restricted to the NHL.

“It’s kind of like a little cycle,” Pronger adds. “You reach a level and there comes a point where you can take a shift off now and then and it won’t hurt you. Then you go to the next level and you realize you can’t do that.”

Size vs. smarts

Pronger’s game is often keyed by using his size, but he feels that playing smart is much more important than playing big.

“Size has some advantages. Being a rookie, I used my size to help out sometimes,” he says. “I could use my reach to poke check the puck away if I got beat to the side. I mean, you’re not very often going to run a big guy over.

“But playing smart is what you have to do. Get in the right position to begin with, and that guy won’t get around you. Then you don’t have to rely on your reach.”

Another trait Pronger says aids in the “breaking-in” period for a young defenseman is intensity. Pronger cautions against all-out aggression, and is instead in favor of a win-or-nothing approach. Winning, says Pronger, is always the most important thing—at any level.

“I’ve never been too happy when we lost. If we don’t win, I’m not a good guy to be around. Sometimes, that doesn’t win you too many friends.”

It’s a tough balance to maintain—keeping the intensity to win while understanding that a level head is required to effectively contribute to the team despite a lack of experience. And to balance aggression with intelligence.

And it can be murder defensively, where individual mistakes always seem to catch the spotlight. With forwards, the play is more team-oriented. Mistakes result in missed opportunities—which is preferable to outright goals against.

But by the looks of things, Pronger’s all-out approach to winning should carry him through this difficult period of adjustment.

— Bob Cunningham

This first appeared in the 04/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2011 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®

By Bob Cunningham

|

| ©BBS |

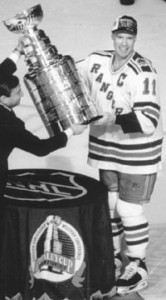

Being an NHL superstar as long as he has, Mark Messier would certainly have the right to harp on personal achievements when asked about the secrets of his success.

But Messier, who has been a member of six Stanley Cup championship teams during his career, most recently with the 1994 New York Rangers, does not. Instead, he focuses on the importance of working well with teammates at both ends of the ice, making whatever sacrifices are necessary for the good of the team, and achieving the only goal that matters: winning.

“The formula for winning is really pretty simple, but most teams don’t get it,” Messier said near the end of last year’s regular season.

“It” is in many ways one of those oft-cited intangibles, which makes it unusual fodder for this column. But Messier had a game plan in mind prior to last year’s Stanley Cup playoffs, and through actions rather than words he imparted that plan to each and every other member of the Rangers. So what exactly was it that let Messier silently express such a powerful message of unity to his teammates?

“Five Cups,” replied all-star defenseman Brian Leetch.

Considering others

Leetch was a key figure in Messier’s scheme. Regarded as one of the NHL’s finest defensemen at both ends of the ice, Leetch’s individual success would go a long way toward determining the fate of the Rangers, and Messier knew it.

So in this case, Messier—at forward—considered the success of his team’s key defenseman in forming his own approach to the game.

“I’m one that tries to help my teammates through my own hard work,” said Messier. “If I’m focused on doing my job, whether that be scoring goals or setting up the attack, I’m taking pressure off everyone else. That’s the way I’ve always viewed it.

“Brian Leetch is a tremendous competitor, and probably the most important guy on our team,” he added. “I really believe that. He was our defensive leader, so I’ve taken upon myself to go out of my way to complement his game.”

And Leetch has taken Messier’s example to heart, as well. “He’s a star,” said Messier, “because he has the same attitude (as I have) toward the forwards on our team.”

Don’t play for the moment

Messier explains that everything he tries to accomplish on the ice has an ulterior motive. Perhaps one of the main reasons for his long-term success, both on individual and team levels, is bred from his ability to see into the future—to anticipate.

“I try to anticipate what’s going to happen, help see what my teammates might need in certain situations,” he says. “But I think all good hockey players do that. You can’t just play for the moment.”

While anticipation is usually a sign of sound instincts, Messier doesn’t think it’s a case of the “have’s” and the “have-nots.” He insists that a player can literally “teach himself” to predict the future.

“You make it a practice (if you’re a young player) to observe the result of certain situations, so that you can recognize it when the time comes again,” he says. “That can be certain plays a team makes, or trends by a specific player, or whatever.”

Getting to kiss the Cup isn’t quite so simple, however. Messier chuckles at the thought of giving tips on how to win championships.

“It’s not that (winning Stanley Cups) just happen, because I’ve worked very hard for the success I’ve had,” he says. “But I’ve been fortunate, playing with guys like Brian and Mike Richter and, oh yeah—Wayne Gretzky has had something to do with it, too.”

“It’s a team game”

Dedication to a common goal is everyone’s job, Messier says, but forwards—specifically, centers—tend to be viewed for their individual contributions to a game, much like a quarterback in football.

“A lot of people, including a few guys I know in the NHL right now, believe that if you’re the center it should fall on your shoulders,” Messier explains. “But obviously, it’s a team game. The best advice I can give, I think, is for a player to always remember that, regardless of what level he plays on.”

Messier points to several NHL forwards—he wouldn’t name names—that simply refuse to do anything that goes beyond the classic job description for their position.

“There are certain times over the course of a season, or of a game, where you’re called upon to do things you’re not accustomed to, or expected to do,” Messier says. “Every time I throw a check, my coach cringes because he wants me to stay away from the rough stuff. But if I have to risk getting hit in order to protect the puck or to create a turnover that gives us a scoring opportunity, that’s what I’m going to do.

“The day I stop thinking that way is the day I hang up my skates.”

Bob Cunningham is a Southern California-based freelance writer who contributes to several sports publications throughout the U.S. and Canada.

This first appeared in the 01/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2011 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®

Brothers and Sisters’ star Dave Annable, native of Pittsburgh, suits up for the White team.