Breakout basics

By Bill Ferguson & Quint Randle

|

| Breakout 1 |

Have you ever noticed how effortlessly NHL teams breakout of their zone? Why is this? Wouldn’t it stand to reason that if the opposing team put enough pressure on your D, that would make it tougher to break out?

In truth, it does. But pro players have the experience to know that, short of being outskated, anything the other team does can be countered. There is nothing that forces the other team to respect you more than the ability to break a man out quickly and send him in alone on their goalie. The team that regularly gives up more breakaways than their opponents do will have trouble winning.

So how do you know where to go, and when?

At the risk of belittling America’s most popular team sport, hockey is not as simple as football, where you line up two guys to bash heads together, and the biggest or strongest guy wins. Hockey is a thinking man’s game (or so we like to think!). The key to gaining an edge over your opponent is the ability to anticipate what the other team is going to do. If you can do this, you can counter it.

Forwards need to develop the instincts to know when to drop the defensive coverage in their own zone and go to their position for a breakout. Defensemen love the forward who is always open for that first pass, and always hits his man for the second pass. This guy is the “wheel” who makes your whole breakout happen.

Be the “wheel”

All forwards need to learn to be that guy, and the best way to learn is to watch the guys who are already good at it. You’ll notice they all play “heads up” hockey, and already know where they want to go with the pass before the puck gets to them. A forward who waits until the puck gets to him before deciding where to go with it won’t get the job done. So learn to anticipate.

There is nothing as frustrating for a team as spending an entire shift trying to break out of your own zone and being unsuccessful. If this happens to you regularly, you’re either in the wrong league, or you’re doing something (or a lot of things) wrong. Let’s look at some ways of improving the breakout.

Breakout One

First of all, let’s make sure everyone is in the right place. Wingers, your job is to cover the points, making sure the opposition’s two defensemen don’t have a free shot at your goalie. You must be close enough to their D to cover them, and hopefully so close their forwards won’t even attempt a pass to them. This limits their options. Center, your job is to help your defense, either by covering their center, or covering whoever is open in front of your net. D, you know what to do. Then, once your team gains control of the puck, everyone’s job description changes.

This is the simplest breakout in the world. One D takes the puck behind his net. Most forecheckers won’t chase him there. Prior to this, as soon as your team has gained control of the puck, the two wingers covering the opponent’s D should come back a little deeper in your zone—usually between the faceoff dot and the top of the circle, right against the boards. By this time, at least one, if not two of these wingers should be open.

Seeing this, the D with the puck skates to the side of the net with the least pressure and passes to that wing. This first pass is the most critical one in the breakout. It must be perfect—on the ice, right on the tape. When your team first gains control, the center starts to circle, always keeping the puck in sight.

As the first pass goes to a wing, the center starts to angle toward the faceoff circle outside your zone, on the side where this first pass went. His movement allows the wing who received the first pass to hit him on the fly, and (hopefully) he’s gone. The idea here is that as your center angles toward the neutral zone, their defenseman must go with him or risk a breakaway. This should always open up some passing lanes for you, either for hitting the opposite wing with a cross-ice pass, or allowing the first winger to skate the puck up himself. If their defenseman pinches in on the first wing, the wing must either pass around him or backhand it off the boards, which should still result in a good breakout for the center.

Two things are critical with this breakout. 1) The winger who gets the first pass must control the puck. He should be standing with a skate perpendicular to the boards to prevent the puck from sliding under him. His upper body should also be against the boards, so the only puck that can get by him is either flipped up in the air or banged off the boards at such an angle that he can’t get to it. If it’s the latter, the center will often pick up the puck. 2) The wing who gets the first pass must clear the zone with his pass. If the winger misses the first pass, it goes right to their D—meaning not only are they still controlling the puck in your zone, but now your center has just skated out of the zone, so they also have an outnumbered attack. However, if everybody does his job this won’t happen.

|

| Breakout 2 |

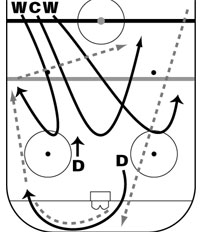

Breakout Two

To open up some ice for your breakouts, try floating a wing out at the red line. This “floater” has to be one of your fastest skaters, because he not only must be able to outskate their D, he also has the responsibility to come back and help out if the puck doesn’t get through to him. If your D can hit him with a long breakout pass, their D will not be so quick to pinch in on your breakouts. If you have confidence in your D, and the ice time to practice breakouts, you can have your center flying and ready to receive the quick pass from a wing stationed on the red line.

This epitomizes what “the worlds fastest team sport” is all about. If you can make this play work you can really string out their defenders and create some good scoring chances. There is no need to wait until late in the game when you’re down a goal to try this play. I suggest trying it early on, which will force the opponent to respect the play, and open up some passing lanes for your breakouts. Your offense will “flow” more smoothly if you have the open ice to make some good, long passes.

And what do we mean by flow?

When you think “flow,” chances are you think of the Montreal Canadiens. Their transition game (going from D to offense and back) has always been one of the best in the NHL. This is partly because their players always seem to be in position. When you watch them, notice that there are three, four or even five Canadiens in the play. They move up and back as a unit. This is team hockey.

They also practice. Most players at the amateur level get little or no practice time. If you want to look better as a team, and have more fun playing hockey, rent some ice time (you can split it with another team) and practice your breakouts. There is nothing like practice to help give you the instinct to make the proper play. Practice until it becomes second nature. While you’re at it, work on your defensive and offensive face-offs, too, so everyone on your whole team knows who has who and who goes where. There is nothing in hockey more exciting than the bing-bang-boom passing play that results in a goal. These things don’t just happen by accident; you have to work on it.

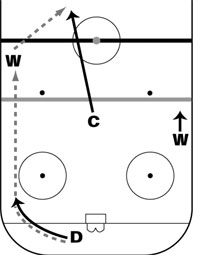

Flow Drill

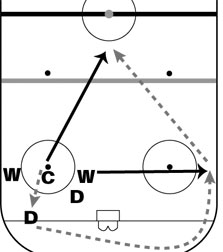

Here’s a great drill to help foster flow between your forwards and defensemen (see diagram below). Pretend the opposition is doing a dump and chase into your zone (although there is no actual opposition in the drill). The coach is stationed on one side of the ice at the red line with plenty of pucks. Your forwards are on the opposite side of the ice, ready to return to their zone. The coach dumps a puck into your zone and the appropriate defensemen picks up the puck. As the coach dumps the puck, the three forwards break back into their zone and “swing” back the other way, usually no deeper than the tops of the circles. As the defenseman gains control of the puck, he then passes to one of the wingers.

As in the diagram, the D swings around the net and passes to the left wing, who has swung in towards the boards. The winger then moves forward and passes across to the center. At this point the drill can become a standard three-on-two exercise with two D and an opposing goaltender in the other zone.

Trick Plays

No article would be complete without a few trick plays that can help you late in the game. If you have a defenseman who can flip the puck high, and a center who can win a faceoff in your zone when he has to (as well as being one of the fastest guys on the ice) then check out Trick Play 1. It’s fairly easy to face-off deep in your zone, have the center draw the puck back, then take off up ice. Some defensemen won’t notice him if the puck is still deep in your zone. By the time they make the decision of whether or not to go with your center, it’s too late. Your D flips the puck over their D at your blue line and there’s no one to pick it up but your breaking center. This play can obviously only be rarely used without revealing itself to the opponent.

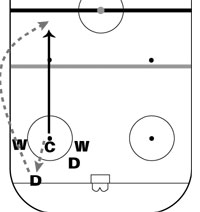

A more conservative variation on this face-off play is shown in Trick Play 2. If your center wins the face-off clean and draws it back to your D, the winger on the far side of the ice takes off as soon as the faceoff is won, and breaks laterally to the far boards. This predetermined play allows the defenseman to bang the puck behind the net to his far wing, who should have a fairly high-percentage pass to your center.

In the attacking zone, a trick play that works well is for your center to tie up his man, then kick or pass the puck slightly in front of the net. If their D is napping and allows your wing to get by them, he should have a chance to redirect this pass or get a clean shot.

|

| Flow drill |

|

| Trick play 1 |

|

| Trick play 2 |

This first appeared in the 04/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2011 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®