Getting your gear in game shape

By Bill Ferguson

|

| Yuck! Falling foam liner. |

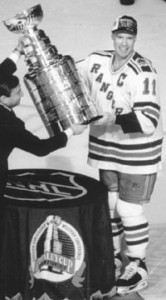

Picture this. The Madison Square Garden crowd goes crazy as the singer belts out the last line of the Star Spangled Banner. Wayne Gretzky skates to center ice for the opening faceoff of the 94/95 Stanley Cup finals against his old buddy, Mark Messier. Just before the ref drops the puck, Gretzky notices his right skate lace is broken and getting looser with each heartbeat. What does he do?

A. Call time out.

B. Get another center to take the draw.

C. Tell the ref to hold that thought.

D. None of the above.

The correct answer, of course, is “none of the above.” Why? Because odds are this would never happen. This is a pro player we’re talking about, and as part of his pre-game routine he already checked his laces.

I know what you’re thinking. It happened to Tonya Harding, didn’t it?

Well, that’s different. That’s figure skating, and this is hockey!

If your game in the local league is as important to you as the Cup finals are to Gretzky, or the Olympics were to Tonya, then you need to get serious about your equipment. Everyone talks about being mentally and physically ready once you’re on the ice, but what about the hardware? How can you make sure your equipment is also game-ready, head to toe?

Just read on, my friends.

Heads first

We’ll start at the top. Regardless of what you young studs think, the helmet is your most important piece of protective gear. It should be thoroughly inspected regularly, as well as any time it sustains any significant impact. Look for any cracks; no matter how minor they may appear they can allow serious injury to occur, and will certainly invalidate the manufacturer’s warranty. Replace a damaged helmet at once. Also check all screws; replace any that may be corroded, and tighten the others.

Something else to look for is the gradual hardening of the protective foam liner, which is caused by sweat and heat. One thing that will lengthen the life of your foam equipment is keeping it away from heat. In other words, avoid leaving gear in your car during the heat of summer, Einstein, and don’t dry it on the radiator in winter. And remember, this applies to all your equipment, not just helmets: hockey gear doesn’t dry in a bag—it rots.

But back to the hat: once the liner becomes hard, the protective capabilities of the helmet are diminished, so from time to time take the plunge and get a new lid! If the foam is still pliable yet separated from the plastic, the only glues that will work are hot glue, or weather strip adhesive. These may also invalidate your warranty, so check with the manufacturer.

It will also be necessary to replace the plastic and metal snaps on your chin straps. Likewise, the hardware for cages and visors.

Larry Bruyere, co-owner of LA’s All Star Hockey & Sport, says maintenance is a high priority with his patrons. “On a Saturday we will have one guy doing nothing but helmet maintenance all day long. Also, I discourage some parents from buying a top of the line visor/cage combo unless the kid is responsible enough to keep the helmet in a bag or shirt every time he puts it (away). Everything in your bag,” says Bruyere, “whether it’s metal or plastic, will scratch your visor, so a little prevention will go a long way.”

Whatever you do, don’t belittle the importance of your most important piece of protective gear: either do your maintenance or replace your toque.

Below the neck

Shoulder pads shouldn’t require maintenance, as such, yet should be checked occasionally for damage. The experts at All Star Hockey stress a proper fit as being most important for shoulder pads. It is often better to buy a less expensive model which fits properly (no excess space between the shoulder and the pad), as opposed to buying a more expensive model which restricts movement be-cause it’s too large or too small.

The same holds true for elbow pads. No matter how good your elbow pads feel, they won’t protect you if they end up in your glove. Buy only pads which feel good and are snug enough to stay put. Many manufacturers are going to the old Jofa-type design that features a big elbow cap which protects well and stays in place. If you find yourself constantly sliding your elbow pads back into place, get some new ones that fit, or get some new elastic and Velcro sewn on.

And now, the mitts. The most common maintenance problem with gloves comes from wear and tear. If you buy the best gloves you can afford, they will last longer and protect better. (Players with cheap gloves get their hands broken, by falling and from slashes). But when the time comes for maintenance, the better gloves can usually be repalmed for around $60. If they need the gussets between the fingers, too, figure $75. This will double the life of your gloves. If you have cheap gloves with no palms left, the best maintenance I can suggest is to give them to the dog and get yourself some new ones. Day-to-day, protective “leather dressing” is not recommended for hockey glove palms. Instead, just make sure you dry the gloves well between games.

Parents, never buy over-sized gloves for kids. Your child won’t have as good a grip as he should on his stick, and he will blow out the side of his palm—so the money you save by “buying for growth” is wasted by premature equipment failure.

No, not Stanley

Le cup. And, no, I don’t mean Stanley. It should be comfortable. If you have trouble with chaffing, try the new “banana style” cups, which are more slender. Above all, your cup, long johns, and any other piece of clothing which touches your skin should be washed regularly. This may come as a shock to even experienced players but yes, you can wash most of your hockey gear. Gather up everything but your skates, helmet and gloves and put them into a tub of warm water and Woolite once a year. This will not only keep them from smelling, it also helps disinfect. There is a bacteria which can form in wet hockey gear which causes a condition called “The Gunk.”

Don’t laugh—it has ended the career of pro players and can be rather painful, causing red blotches all over the body. The best way to avoid this is to take your gear out of your bag and let it air dry after every game. That’s right, your bag is not for storing your gear unless it is thoroughly dry. Get in the habit of doing this and your gear will not only smell better, it will also last longer. Your teammates and family will love you for it.

Maintenance for your hockey pants is pretty simple; an occasional washing, and quick repair of any small tears. I say “quick” because a small tear, without some attention, will soon become a big hole. Here’s where that old hockey saying—”A stitch in time saves thine… pants”—comes from. All right, so maybe it’s a new saying, but it still applies.

The only other thing to remember about pants has to do with buying them. While padding is critical, and something to be looked for, it is possible to overdo it. Pants with too much padding can sometimes restrict your movement, so it might be better to go for pants that offer a tad less protection with a little more freedom of movement.

If the helmet is the most important piece of protective gear, the shin guards are the second most important. According to the experts, many people buy shin guards that are simply too big—and that’s easy to do if you try them on without wearing the rest of your gear. They may feel great in the shop, but if they don’t work well in conjunction with your skates and pants they will hurt your game. Also, look for shin guards that have what’s called a “sling,” the piece of material that suspends the pad away from your leg, and offers the best impact protection.

The only other care required for shin guards is to check them regularly for cracks. Many players have sustained serious injuries, some career threatening, by trying to “milk” one more game or Practice out of their old cracked pads. Don’t risk it. You’ll play more confidently and aggressively with new pads. One thing I must mention about shin guards is that they should only be taped below the knee—never from the knee up. Taping above the knee can easily restrict the flow of blood to the feet. If you tape high-up, and get “lead feet” halfway through the game, try taping your pads to no more than a couple of inches below the knee.

Who said that?

When it comes to skates, we will start off by dispelling a myth. Pro’s don’t change their laces every game. But, according to Dave Taylor, veteran of 17 NHL seasons with the LA Kings, they do check them before every skate. “And if there’s any fraying at all,” says Taylor, “they will change them.” And always lace your skates the so-called Canadian way—which means lacing over the top, from the outside in. This allows the lace to bind down on itself at each set of eyelets, which not only makes it easier to get your skates tight, but keeps the laces in place.

There is no other piece of equipment you wear that affects your game more than your skates, so they deserve regular attention. First, check the blade and make sure it is tight in the blade holder. With the advent of the new lightweight blade holders came some new problems. If you have an older skate that has a loose blade, you must pull all the rivets, tighten the screws inside the holder and re-rivet it back on. Some of the new Bauers have caps inside the boot that allow easy access to the screws inside the holder. Pro trainers love this feature because it allows them to tighten, and even change, a blade during a game. While you’re at it, check for the obvious nicks and dings that slow you down.

I always “stone” my skates prior to each game to remove small nicks, but if they’re very noticeable, get a sharpening. Generally speaking, the more experienced the skater, the less of a hollow you want on your blade, Defensemen usually want their rocker more to the back of the blade and, of course, forwards normally want their skates rockered more toward the toes—to shift their center of gravity further up on the blade.

Inspect your boots regularly for damage. The first thing that will go on a skate is the inner liner. If your liners are cracked badly enough to cause irritation, cut loose with your check book and get some new ones. Also, check for loss of stability at the ankle. If your skates have lost their support there you won’t skate well, so they need replacing.

These maintenance steps are designed to maximize both your investment in hockey gear, and your enjoyment of the game itself through improved performance. Few things in life are more fun than doing better—better than your last time out, and better than the next guy. Remember, “He who dies with the most goals wins!”

Bill Ferguson has been playing and coaching hockey for over 20 years.

This first appeared in the 02/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2011 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®