Playing D with Phil Housley

By Bob Cunningham

Oct 29, 2001, 19:41

|

| ©BBS |

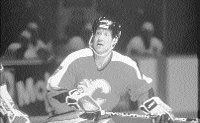

Perhaps only Paul Coffey is more renowned than Phil Housley for his scoring among defensemen. Housley, now with the Calgary Flames, is in his 13th NHL season, a tour of duty that included stops in Buffalo, Winnipeg and St. Louis. And without a doubt, the smooth-skating blueliner has had his greatest impact on the game in the offensive end.

But the first thing Housley points out when asked to assess his game is the gradual improvement in his defense. Relatively undersized at 5’10” and 185 pounds, Housley has increasingly relied on savvy and anticipation to ward off would-be attackers. And when they make a mistake, he’s there to capitalize in the form of a goal or assist.

“I’ve been known primarily as an offensive defenseman, although I kill penalties at times,” Housley explains. “My best assets are seeing plays develop, getting to the puck first and making that good first pass.”

For most defensemen, offensive-minded or otherwise, anticipation is a vital requirement. According to Housley, players who try to get by solely on reaction are usually a stride behind the play—which is often the difference between preventing a goal and allowing one.

“Seeing the play develop before it happens, I guess that’s something you get better at with experience,” he says. “On defense, I try to know when the shot is coming and then maintain position.

“My defense has come a long way.”

Housley’s lack of bulk can be detrimental at times, but he’s done well with his ability by adjusting to alter a forward’s path at the right moment.

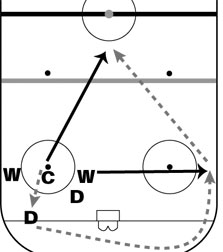

“If I know when the shot is going to be tried, I’ll try to use my body to get in front of a guy who’s in front of the goal,” Housley explains. “There are a few ways to stop a play in the middle. Pushing a guy in his lower back, and timing it so that you can move out of the way of the goalie’s line of sight. That’s something I try to do whenever I can.

“You’re not going to move a 200-pound player away from the front of the net, so what you have to do is try your best to interrupt his timing, which usually stops the play. There are ways to do it.”

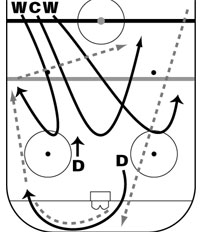

Still, Housley is at his best in the open ice, leading the transition and setting up for scoring opportunities.

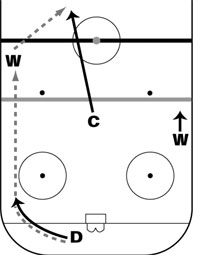

“I try to create offense from behind the play,” he says. “Finding the open man during transition and creating opportunities through turnovers. Creating offense from your own end, without taking a lot of chances. You can’t afford to be loose with the puck anywhere, especially in your own end.”

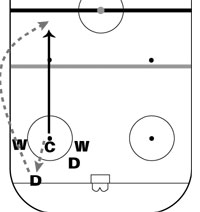

Housley points out a common error made by young defensemen.

“They don’t put enough emphasis on good passes in their own end. Too many risky passes,” he laments. “Sometimes I’ll see inexperienced players trying a backhand pass in their own end. They get out of position, and they try a tough pass to get out of trouble.”

Skating, stickhandling, hard work

A way to counteract mistakes, says Housley, is through a technique he passed on to younger players when he was involved in youth hockey clinics earlier in his career.

“I used to work mainly with skating and stickhandling,” he recalls. “I would have them see themselves in their heads playing the game. They would visualize what to do out there.”

Housley believes you can never work too hard at your craft. The longevity of his career speaks for that.

“It’s mainly hard work. The less time you spend in your own zone, the more time you should have to handle the puck.”

Housley has handled the puck in the opponent’s end enough to record 838 points in 886 career games. His best season came in 1992-93, with the Winnipeg Jets, when he finished with 97 points (including 18 goals) in 80 games.

His first eight NHL seasons were spent with Buffalo Sabres, where he remains that franchise’s all-time top scoring defenseman. He was dealt to the Jets in 1990 in the trade that brought Winnipeg’s all-time leading scorer, Dale Hawerchuk, to Buffalo.

Having undergone major back surgery last season after playing only 26 games for the St. Louis Blues, Housley is surely closer to the end of his career than to his prime. But after being traded to Calgary (for another top offensive threat from the blue line, Al Macinnis), he’s still a major contributor to the team, despite what he sees as a trend toward bigger, more physical defensemen.

“There’s no doubt that the kids are getting bigger and stronger and more physical,” he says. “You see that all around the league now, and even in the minor leagues. The exception is kids like (Anaheim’s) Paul Kariya, young players who see the ice well.

“To be successful you have to have the right chemistry. You have to have a mixture of bigger and smaller. Guys that are fast, and guys that are physical. I think some (teams) are getting away from that a little. They want size.

“Everyone wants bigger players. There aren’t as many players like me as there used to be.”

But big or small, the position must still be played correctly.

“Well,” says Housley, “you have to know what you’re doing out there. That’s for sure.”

— Bob Cunningham

This first appeared in the 05/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2011 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®