Skating with the Ref

By Alex Carswell

Nov 6, 2001, 19:24

|

| Leary can poke check too. ©BBS |

Hey, you. Yeah, you, with your nose in the magazine. Who do you think of when I say “in-your-face” hockey? Huh?

Cam Neely? Marty McSorley? Ulf Samuelsson?

Try Denis Leary.

You know, that guy in the Bruins jersey urging Wayne Gretzky to work on his passes in ESPN’s 1994 NHL playoff promos? The guy who bitterly calls #99 a puck-hog?

The Boston-born actor who pioneered the “in your face” brand of entertainment so popular today, first for MTV and then in a series of memorable Nike ads that changed the face of marketing to Generation X, is definitely into puck. Big time.

“I’ve been playing since I was four or five,” says Leary. “There are rinks in every neighborhood where I grew up. Our high school was about four blocks from my house, and the rink was like another four blocks after that. The high school team, my bantam team and even the spring and summer league teams all played in the same rink.

“Plus, we’d also do the rink-rat thing — picking up tape, cleaning up — and then skate at 2, 3 o’clock in the morning. You couldn’t get away from ice time when I was growing up.”

While Leary, now 37, proved better suited for a comedy and acting career than one in pro hockey, he did have his moments.

“I played high school hockey at St. Peter’s, in Worcester (MA), and at the end of the school year central Mass used to play eastern Mass. So we were the team that would win and come out of central Mass, then go play in Boston Garden and get our butts kicked by whoever made it from the east.

But it was still a great experience skating at the Garden.”

Plus, how many of those high schoolers who kicked Leary’s butt ever got to skate with The Great One?

“We had a blast shooting those promos,” says Leary, who now lives on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and had been off the ice for a few months before the shoot. “I hurt my back (the previous) November, and I hadn’t been skating with my team in New York. So I was trying to work my way back into shape when the ESPN thing all fell together. So I flew out to L.A. and we did three spots.

“We shot them all in one day, so I ended up skating for nine hours — Gretzky skated for five — and it was great. It was the first time in my life I ever got paid to skate, and that was great, but I didn’t do it for the money. I did it because I got the chance to skate with Gretzky.

“But nine hours on the ice is tough. After about six you just start going on pure adrenaline. There’s nothing else left.”

Where’s The Game?

When Leary’s not skating with Gretzky, he’s skating somewhere.

“It’s nuts, and it’s probably because of Gretzky, but it’s easier to find ice time in L.A. than in New York.”

Leary finds himself in L.A. more and more these days, now that his film career is taking off. “You can skate five times a week if you want, and not late at night, either. I’m talking morning skates, early evening skates…and quality games, too, because there are all these guys from the east coast and all these Canadians who’ve moved down there for business or whatever.

“Meanwhile, in New York, you’ve got to fight left and right just to get late night ice time. It’s not good for hockey.”

And, of course, the “regular guys” Leary plays with in New York are replaced by higher-profile sorts in Tinsel Town.

“There’s a Sunday night game that the producer Jerry Bruckheimer has, and it’s a good game. It has all different levels: the first line is guys who can really go, the second line is guys who can kind of go, and the third line is the old guys. Then there’s a game that Alan Thicke has on Tuesday and Thursday mornings that’s a terrific game, with a lot of ex-pros and guys just out of college.

“It’s a good, hard skate for me. And because I’m 37, it kind of puts it all in perspective.”

The lack of available ice time in New York, plus his four-year-old son’s newfound interest in skating, has also turned Leary on to in-line skates. “I’ve got a pair of Gretzky’s new in-line skates and Jack has a pair of Rollerblades, so I’m going to start taking him out to the park. I’ll try and teach him the game and maybe work on getting my legs back.”

Now that he’s getting lead roles, Leary has to worry about more than just his legs. He has to worry about his face, too.

“In high school, like everyone else, I just wore the old Butch Goring three-piece helmet, so that’s what I was used to and I couldn’t play with anything else. Later on, I tried the shield, and I didn’t like it because it kept fogging up, so I said ‘screw this.’

“Then, back in ‘88, I got hit with a stick and took three or four stitches — which had happened to me a million times before — but suddenly it occurred to me ‘Hey, I’m an actor.’ And I realized if somebody takes my eye out I’ll be stuck playing one-eyed bad guys the rest of my life. So I went to the cage, and eventually got used to it.”

At the moment, Leary is also considering trading up from the same pair of CCM Ultra Tacks he’s used since 1982. “I’m thinking of getting a pair of those new Bauer Supremes with the graphite reinforcement. They’re supposed to be terrific skates.”

Big Bad Role Models

Leary, a right-shot who plays either wing, says his style is “old school,” and considers Derek Sanderson his primary hockey role model. That seems fairly appropriate for a guy who first became famous for looking threatening and sucking on a butt.

“I grew up on the Big Bad Bruins, and in high school, because we had a pretty good team, I used to play third line. So I became enamored of Sanderson, who was a big hero to all the kids in Boston at the time — he taught us how to smoke, how to drink, and how to sweep check.”

The Turk also gave Leary one of his all-time hockey highlights. “In a meaningless game against Vancouver, Sanderson was forechecking this defenseman. The guy took the puck behind the net, waiting for his wings to set up. So Sanderson stood in front of the goalie, jostling side-to-side every time the defenseman did. Finally, the goaltender leaned up against his post and turned his head to see what the defenseman was doing, and Sanderson just grabbed the crossbar, jumped halfway over the net, swept the puck off the guy’s stick, pulled it out front and scored.

“Both the goalie and the defenseman argued that it shouldn’t be allowed, but the ref had this look on his face that said ‘I never saw anybody do that, so I guess it’s not against the rules. Goal.’ It was great.”

But the demanding physical Leary-as-Turk style of play eventually gave way to a less punishing approach to the game.

“I used to fly full-speed into guys and play the checking game, but watching Gretzky play I realized that you can still be in the middle of trouble and manage, by being smart, to avoid the physical punishment. Obviously, no one does it like Gretzky — he’s got some incredible genetic gift because he can see stuff coming that no one else can. But I’ve started to learn over the last 10 years how to make contact if you have to, but that if you stay in motion — especially in the offensive zone — you can see the contact coming, avoid it, and still be in position for a pass or a scoring chance.”

One has to wonder if Leary’s busy career — he’s currently working on two feature films, a one-man show, and is a contributing editor to Details magazine — will be cutting into his ice time.

“No way. It’s kind of a Jones thing at this point. I can’t not play hockey for too long a period of time or I go nuts. I’ve got a puck on my back.”

As for combining his two passions, acting and hockey, Leary is emphatic. “I’m desperate to do a hockey movie…if I could find a good script. It’s got to be a movie like Bull Durham, where it’s about the characters and hockey is part of what they do.

“All most people want to do is either take advantage of the violent aspect of hockey or, like with The Mighty Ducks, turn it into a kid’s movie. They’ve never made a truly great hockey story, and when they try they get these guys who can’t even skate, and they have to shoot everything from the waist up — which is ridiculous. There are enough guys now who can skate that they shouldn’t have to do that.”

Got anybody particular in mind, Denis?

“All I know is, I just want to get paid to go to work every day and skate. That’s my goal. Just get up every morning, strap ‘em on, and get paid for it.”

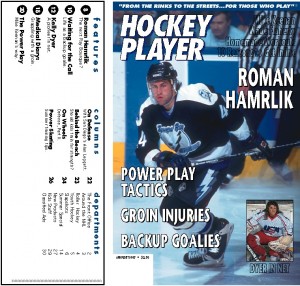

This first appeared in the 08/1994 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2001 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®