Training to win

By Dr. Michael R. Bracko & Dean Lyons

Oct 29, 2001, 20:33

|

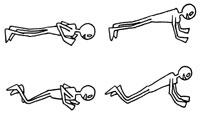

| Jumping jacks: 20 reps (Illustrations by Matt Busch). |

Before beginning any exercise program, please consult with your physician.You play once, maybe twice a week. Your games start when “normal” people who do not understand your addiction are just going to sleep. You have done all the right things by eating a good sports nutrition meal the night before the game, and you’ve been “hyper-hydrating” by drinking Gatorade until your blood turns “Gatorade Green.” You lace ‘em up, thinking you’ve done everything right, and you’re ready for the game of your life!

But, as you do during most games, you get ridiculously tired half way through your shift. The puck starts to feel like it weighs 10 pounds, and you come to the bench not so much because you are tired, but because you need to lie down.

Wondering how to prevent these feelings of extreme fatigue and improve your performance on the ice? Then, man, are you reading the right article!

Playing puck once or twice a week is simply not enough activity to maintain a high level of fitness. And it is certainly not enough to maintain a high level of performance. But, the good news is that there are many off-ice activities that you can do to improve your fitness level and subsequent performance on the ice.

What affects performance

Let’s start by identifying the most important factors that affect performance. They are:

1. Genetics

2. Conditioning and Practice

3. Nutrition

4. Psychology

5. Coaching

|

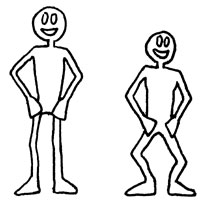

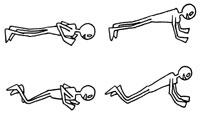

| Push-ups: 10-20 reps (toes or knees) |

There is nothing you can do about genetics, short of some Iron Curtain steroid cocktail, but there is a tremendous amount that can be done about your conditioning. While the other three can also be manipulated to improve performance, those are areas for other experts to discuss. Here, we will concentrate on conditioning.

Next we should outline the most important components of conditioning and fitness for hockey players. They are:

1. Cardiovascular Endurance

2. Anaerobic Power

3. Muscle Strength, Power and Endurance

4. Flexibility

5. Body Fat Percentage

|

| Half-sqauts: 10-20 reps (back straight) |

You will notice that cardiovascular (CV) endurance is at the top of the list. This is not by accident. CV endurance is the most important component of fitness for most athletes because it is the basis upon which most other components are built (see Fitness Pyramid illustration). For instance, when you increase your CV endurance, you will have an increased capacity to perform high intensity anaerobic work, resist fatigue, lower your body fat percentage, and recover more quickly from high-intensity exercise.

When you have a high level of CV endurance you will have an increased ability to use high amounts of oxygen in the working muscles. Higher amounts of oxygen helps in two ways; you are better able to produce energy for muscle contractions, you can clear waste products (such as lactic acid) quicker and more efficiently. The tangible benefits are that your lungs will not be “burning” during a shift, it won’t feel like someone poured battery acid into your legs, and you will recover your wind more quickly between shifts.

In other words, you will be able to “skate all night” and still be able to get out of bed the next morning!

|

| Sit-ups: 10-20 reps (with knees bent, don’t hook feet under the couch!) |

In other words, a high level of CV endurance will prevent extreme fatigue at the end of each shift, period and game. Fatigue adversely affects the fine muscle movements required in shooting, passing and receiving a pass. Therefore, you should be more accurate with your shots and passes, be able to carry the puck, receive a pass, and out-skate most of the players on the ice. Worthy goals, don’t you think?

You play yourself out of shape

The irony of all this is that in spite of its importance, CV endurance actually decreases during the season because most activities in hockey are anaerobic—meaning “high intensity, but short duration.” Professional hockey players now realize that they must engage in some kind of CV or aerobic training off the ice to counteract this loss of conditioning. Most players use an exercise bike, a stair-climbing machine or a skating machine after practice.

But what should you do?

|

| Back extensions: 5-10 reps (lie flat, hands under hips, and raise shoulders) |

As a recreational hockey player you can drastically—yes drastically—improve your performance by doing some off ice aerobic training at least three times a week.

The good news is that aerobic exercise does not, and should not, be high intensity. Rather, the exercise should be at a moderate pace. Aerobic exercise can be described by the following components:

1. Duration of 15 minutes or more

2. Activity of moderate intensity

3. Must involve moving the legs

4. Must be continuous/non-stop

With that in mind, the time has come to prescribe a conditioning program. Again, there are four aspects to consider; frequency, duration, intensity, and mode of exercise.

Frequency is easy to address. In order to improve or maintain your CV endurance you should engage in aerobic training at least three times a week. Four, five, six or even seven times a week is fine, but considering that you play hockey once or twice a week, three days per week is recommended.

Duration—the amount of time you work out—can vary according to your initial level of fitness, time constraints, motivation, and the activity you choose. Generally speaking, you can get a good training effect from 20 to 30 minutes of aerobic exercise, but the minimum amount of time we can exercise and still get a benefit is 15 minutes. The maximum amount of time? Well, that depends.

When you first start an aerobic conditioning program (weeks 1-3) you should only be working out for 15-20 minutes. During weeks four and five, increase the time to 20-25 minutes. Weeks six and seven, try 25-30 minutes. After two months, you can try varying the length of your workout, making sure you are getting at least 15 minutes.

|

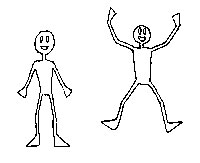

| Hockey hops: 20-40 seconds (with knee bent, hop from one leg to the other while extending the non-landing leg) |

Ego figures in

Intensity is a tough factor to address for two reasons; ego, and the tradition of athletes being trained to always workout “hard.” The ego is such that many of us still believe the misconception “No Pain, No Gain.” In fact, when it comes to aerobic training this is simply a myth. Most athletes (or ex-athletes) are taught that the key to success is “hard work,” and this is true in most cases. However, it is not true with aerobic exercise. The truth is that you should always perform aerobic exercise at a moderate pace.

There are many ways to determine the correct intensity at which you should be exercising. One method of determining exercise intensity is an objective measure, and the other four are subjective. The objective method of monitoring the intensity of exercise is by calculating your “Target Heart Rate” using the five-part formula in the accompanying box.

The target heart rate works as follows. You will get maximum benefit from aerobic exercise when you keep your “exercising heart rate” (EHR) between the numbers (rounding up or down) that you calculate for the 60% and 70% levels (for weeks 1-4). After week four you will want to increase the intensity of the exercise so that your EHR is between the 70% and 85% levels.

|

| Shoulder presses: 10-20 reps (use hand weights) |

Your EHR is beat taken on your wrist every five minutes during your workout, for six seconds (just add a zero to your pulse number, and you have your Target Heart Rate).

Here is an example: Let’s say you are 32-years old with a resting heart rate of 72. Your Target Heart Rates will be 141, 153 and 170 for your three exercise levels (rounded, they are 140, 150 and 170). During weeks 1-4 of your program, you will want to keep your exercising heart rate at 140 or 150 in order to receive maximum benefit from the exercise. If your heart rate is at 170 or 180, you are exercising too hard. And if your heart rate is 100 or 120, you are not exercising hard enough and you need to increase the intensity. After week four, you should increase the intensity by exercising with your heart rate between 150 and 170.

The other methods of monitoring your exercise intensity are much more subjective and are based entirely on how you feel. The “Talk Test” indicates that if you can carry on a relatively normal conversation while exercising then you are working out at the correct intensity. If you are exercising so hard that talking is impossible, you need to slow down. The true meaning of “aerobic” is “in the presence of oxygen.” When you do aerobic exercise you want oxygen demand to meet oxygen supply; in other words, you should be breathing hard but not to the point where you are gasping for air.

|

| Half-squats with a hop, 10-20 seconds |

Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) indicates that if you feel like you are exercising too hard, you probably are—and you need to reduce your intensity. By the same token, after you finished exercising (immediately after or the next day) if you feel like you worked too hard, you probably did. If you can’t got out of bed or climb stairs because you are so sore, you really need to decrease the intensity of your exercise.

On the other hand if you feel like the exercise is not hard enough you should probably increase the intensity. If you feel pretty good the next day, then you are most likely doing the right thing.

Some days are better than others

Another way to determine your exercise intensity is by your Subjective Energy Level (SEL). Some days you may feel really good, with a lot of energy, so you may want to exercise harder and/or longer. Other days you may feel tired—but still want to work out—so you might decrease the length and/or the intensity of your workout.

Yet another way of determining the correct exercise intensity is by using the “Reading Test.” If you are reading while riding a stationary bike or using a Stairmaster and you cannot comprehend what it is you’re reading, then you are probably exercising too hard.

There are many types of exercise from which you can choose. You should keep in mind, however, a rule of conditioning called “specificity of exercise,” which means that you should emulate the movements of the sport for which you are training. So, with that in mind, here are some of the most hockey-specific aerobic activities that will improve your CV endurance; in-line skating, slide boarding, stair climber machine, stationary bike, and step aerobics.

|

| Reverse flys: 10-20 reps (arms extended, make sure you’re stable) |

A second group includes some other very good aerobic activities which are not quite as specific to hockey. They are: running, cross-country skiing (or a cross-country ski machine), a recumbent exercise bike, rowing, and rock climbing “treadmills.”

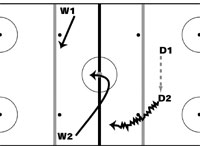

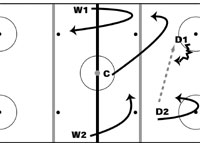

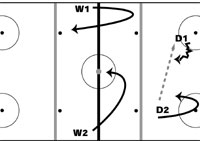

Yet another method of improving your CV endurance (along with your anaerobic power and muscle strength) is circuit training. This type of workout is a better “all-around” activity because you get a little bit of each of three types of fitness; endurance, power and strength.

In a recently completed research study, we analyzed the skating characteristics of NHL forwards and found some very interesting information about the way the players skate during a game. Of particular interest is the fact that the players spent the majority of time (on the ice) gliding on two feet, and struggling for the puck or position also had a higher percentage of time-spent than did skating at full speed. This may indicate that the fatigue experienced in hockey is not caused by full speed skating, but rather by battling with other players for the puck or position. Therefore, a workout that involves “total body movements” may provide a better stimulus for hockey.

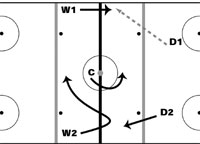

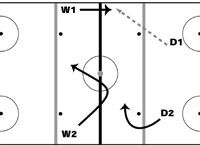

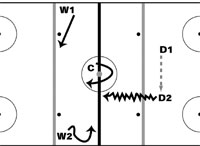

You can perform circuit training at home, with or without weights; at the gym (with weights); or even in the park.

The sidebar shows an example of a circuit which can be done at home. All that is needed is a soft surface (an exercise mat or a rug) and some hand weights. As with any type of exercise, you should always start with stretching and a warm-up, and the first circuit should be performed at a low intensity. One circuit should take approximately 3-5 a minutes, so move through the circuit five, six or seven times.

Whatever you end up doing, always remember the key points of aerobic training—moderate intensity, 20-30 minutes of continuous activity, and always move your legs. And once you’re well into a program designed to increase your CV endurance, you may find you’re also well into your best stretch ever as a hockey player.

Dr. Bracko and Dean Lyons are sports physiologists who specialize in performance enhancement for hockey players.

This first appeared in the 06/1995 issue of Hockey Player Magazine®

© Copyright 1991-2001 Hockey Player® and Hockey Player Magazine®